Secure ledgers don't require proof-of-work

November 6, 2017. @pfrazee

As Bitcoin, Ethereum, and other blockchain-based systems have gained popularity, there’s been a push in the decentralized Web space to use blockchains as a hammer for every nail: databases, user identity, key distribution, and even basic hosting.

I think this is almost a great idea. But, we’re not evaluating the cost of proof-of-work properly, and we need to consider whether we need it at all.

Blockchains and proof-of-work

Blockchains are used to enable networks of computers to run a database without trusting each other. Because the computers don’t trust each other, the network needs a way to make sure that no one is adding fraudulent transactions to the database. In these sorts of cases, a mechanism called proof-of-work is used to help prevent a kind of fraudulent transactions.

In a proof-of-work-based system, adding a transaction to the shared ledger requires the transactor to run a large amount of frivolous computation. Doing computation requires electricity, so all proof-of-work based systems require using large amounts of electricity to function.

This wouldn’t necessarily be a problem, except that proof-of-work systems are architected intentionally to require excess computation in order to meet a requirement of decentralized consensus.

…Which is why we get clickbaity news like this:

The thing is, that headline isn’t totally off-base.

Bitcoin miners are incentivized to spend electricity up to the probability of a win multiplied by the current valuation of a BTC. For a simple example, if you have a 0.01% chance at winning Bitcoin worth $10k, you’d be smart to spend up to a dollar’s worth of electricity per round to win. That’s what’s happening here, all around the world, with rounds occurring every ten minutes.

From the article above:

Alex de Vries, aka Digiconomist, estimates that with prices the way they are now, it would be profitable for Bitcoin miners to burn through over 24 terawatt-hours of electricity annually as they compete. … That’s about as much as Nigeria, a country of 186 million people, uses in a year.

Furthermore, the amount of energy spent will increase as the value of Bitcoin increases, driven by speculation and the need for liquidity in other crypto currencies.

I frequently describe myself as a “decentralization nut” and for me, the cost of using proof-of-work is just too high to accept as the solution to the challenges decentralized networks face.

The more I’ve worked in this space - on Secure Scuttlebutt first, and now on the Dat protocol and the Beaker Browser - the more convinced I’ve become that blockchains are a huge step forward, but proof-of-work is a total mistake.

And, for some people, that’s a surprise. The way cryptocurrencies have been sold to us, it’s reasonable to assume that proof-of-work and blockchains are one and the same. They’re not! Nor do blockchains require proof-of-work to provide value. They’re separate concepts, and blockchains can work alone.

In fact, I argue that proof-of-work is a political solution tacked onto blockchains - a hail mary attempt to provide a cure-all to power dynamics - and it even fails at that purpose.

However! The data structure of a blockchain can be applied to traditional services to introduce incredibly valuable attributes like cryptographic auditability, and it’s the value of that specific use-case I hope to convince you of today.

What are blockchains?

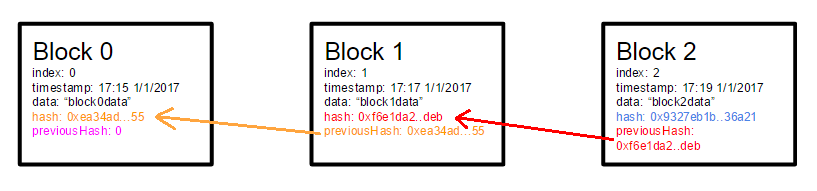

Let’s review the basics. A blockchain is a linked-list data structure in which every entry references the previous entry using a cryptographic hash.

From Wikipedia:

A blockchain is a continuously growing list of records, called blocks, which are linked and secured using cryptography. Each block typically contains a hash pointer as a link to a previous block, a timestamp and transaction data.

Here’s a blockchain visualized (from “A blockchain in 200 lines of code”):

Why do blockchains matter?

Blockchains create accountability.

The hash of each block encompasses the entire chain’s history. If you change one bit of the history, all subsequent blocks’ hashes change.

By encompassing the history in each hash, it becomes easy to compare that history. Two computers can quickly check hash equality with each other to confirm that their history logs match.

A blockchain is supposed to have a single linear history of transactions.

If the compared hashes for a block don’t match, then we know the history has split. A split history is a sign of a lie or corruption, and it means the blockchain author isn’t trustworthy.

Because the blocks are signed, any user with evidence of a split history can prove to the network that the blockchain has been corrupted.

Therefore, blockchains enforce an “append-only” constraint, and enables peers to efficiently monitor the blockchain author.

What is proof-of-work?

Proof-of-work is a system for establishing “decentralized consensus.”

Agreeing about the order of events is very difficult in computer networks, especially if you can’t trust the other computers involved. Unfortunately, it’s also very hard to establish trust in a global network which aims to provide open participation. So, we need a way to agree on the order of events without establishing trust.

Proof-of-work solves that problem by putting the network on a trustworthy clock. It’s a kind of computation which takes a predictable amount of time to run, and which can’t be forged by a bad actor.

With proof-of-work, you can have multiple computers make additions to a blockchain without having them trust each other. That’s decentralized consensus.

Decentralized consensus is intended to mean that one entity can’t control the blockchain network. Any newcomer can participate, and ownership is equally distributed among the participants.

Does it work?

To some degree. Decentralized consensus places control of the network into a purchasable metric. With proof-of-work, that metric is hashing power.

It’s actually a cool idea. Hashing power is created by computing hardware, and you don’t need to ask anyone’s permission to buy computers. So it’s a very populist idea: anybody can get involved at will.

Unfortunately, like any good capitalist system, having capital is a prerequisite to having power when it comes to PoW. Sure your laptop can start mining overnight, but you’re competing in a lottery where the odds of success are directly tied to the amount of capital you invest, and people are investing a lot of money into their mining hardware.

Therefore whether decentralized consensus solves the issue of political ownership is really dependant on circumstance. For the system to stay decentralized, ownership can never be concentrated beyond 50% - but that’s just a question of how much money you’re willing to spend. In fact, because of mining pools, a >50% concentration has happened before. Because you don’t need permission to buy hashing power and participate in Bitcoin, there’s no way a “51% attack” can be stopped, except by outbuying your competitors. Are we certain that will never happen to Bitcoin?

Decentralized consensus also fails to consider the political reality of human networks. The protocols need changes over time, and changes mean governance. In Bitcoin, acceptance of a change is signaled by the miners - once some percent of the miners agree, the change is accepted. This means that hashing power is used as a measure of voting power, and so the political system is essentially plutocratic. How is that significantly better than the board of a publicly traded company?

This is why I’m unimpressed with decentralized consensus as a political solution. Bitcoin has been wildly unstable, with controversies and forks happening quarterly. I personally suspect stability will actually mean “dominant ownership.” It doesn’t seem like a unique victory over political realities, and it still comes with the high cost of proof-of-work.

Ok, what about proof-of-stake (PoS)?

Some folks in the cryptocoin world - most notably the Ethereum project - have been working on a new solution for decentralized consensus called proof-of-stake. It is an attempt to solve the cost problem of proof-of-work, and it involves no excessive energy use.

I like the spirit of proof-of-stake because it tries to solve the problem, but I’m going to point out two things:

- Proof-of-stake is not yet proven, and, prior to proof-of-work, nobody was sure that decentralized consensus was possible. When proof-of-work gained acceptance, computer scientists were running naked in the streets with excitement. Therefore I default to extreme skepticism - but I’ll keep my eye out for any nerdy-looking streakers.

- Anybody who’s been involved in crypto-currencies for more than a year who smoothly transitions from “PoW is a great revolution” to “obviously PoW was never the long term solution” deserves a hard poke in the eye for the duration of my choosing.

I’d explain proof-of-stake here, except that I don’t totally understand it yet. From what I understand, it involves operators placing some of their currency holdings into a shared pot. Then, a random lottery is chosen from those operators, with better odds given for a larger stake. And - I think - you risk losing what you place in the pot if you do something provably incorrect during your turn as the leader.

(That could be wrong. If somebody on HN or Twitter corrects me, I’ll update the explanation here.)

Proof-of-stake could work out. It could be great. I’m waiting to see. Until then, let’s talk about another option that I think can work just fine: services with blockchains.

Services with blockchains

It is the case that blockchains and proof-of-work are two separate concepts, but I worry that the hype around blockchains has inextricably linked the two, so I’m going to switch to a different term to talk about blockchains: secure ledgers.

Conceptually I’m referring to the exact same data structure that a blockchain is, but hopefully “secure ledger” is a bit more descriptive, and most importantly has no baggage or connection to proof-of-work. Got it? Ok.

Services with blockchains secure ledgers

What most people don’t realize is that you can get a lot of value from blockchains secure ledgers without decentralized consensus.

Here’s how:

Instead of a network of miners, you use a single host. That host maintains a secure ledger which contains the host state and its activity log, including all requests and their results. That ledger is then published for clients to actively sync and monitor.

Why? Accountability.

Clients can monitor the ledger, and, just as in decentralized consensus, ensure the host is following a set of business rules. The business rules would be published, either as a set of code files on the ledger, or out of band. The monitors follow the ledger and replay the inputs against the published code. If the outputs or the state on the ledger ever starts to deviate from the rules of the code, you know the host is doing something fishy, and you can prove it.

So, accountability is provided by a very hard-to-forge public log.

With this accountability comes better trust. We don’t need to worry that a keyserver, for instance, is lying about its users’ keys, because we can check its live responses against the ledger. If we’ve reviewed the business logic and trust it, and we never observe a deviation from that logic in the ledger history, then the keyserver is in good order.

That could never work!

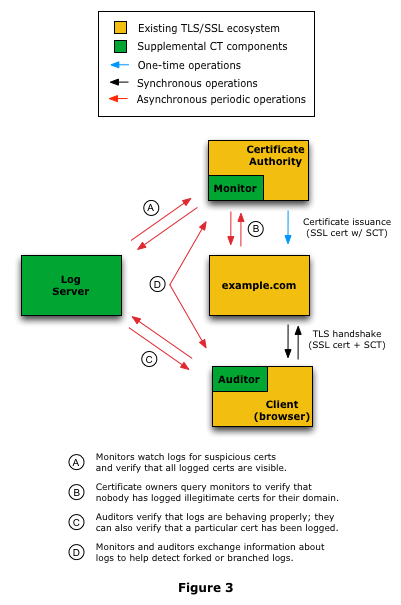

I love to point out when we’re stealing from Certificate Transparency, because it’s a well-respected protocol created by Google to monitor SSL certificate authorities. This is just another one of those cases.

CT is a superb example of this design. Each Certificate Authority maintains a secure ledger of its certificate assignments. Monitor-nodes and clients compare the certs they receive against the ledger to make sure the rules of certification are always being followed. It’s already been used to catch Symantec in the act of breaking the business rules of Certificate Transparency. (Basically, they used a “redaction” feature that wasn’t in the agreed-upon rules.)

A friend pointed out that Git is also an example of a secure ledger - which is true. It uses a chain of cryptographic hashes to secure the history of the code. However, Git wasn’t designed for auditing the actions of a live and possibly adversarial service, and it therefore allows branches and force-pushes, which break the append-only constraint which we need for accountability.

What’s the big win?

Like in crypto-currencies, secure ledgers solve a question of trust for services.

Traditional services are black boxes. We can only guess at what code they are using, and there’s nothing stopping the owners from modifying the DB state.

With a ledger-backed service, you don’t need to worry about surreptitious edits. The only way the state of the service can be changed is by the rules of the published code. That means that the code is a kind of contract; if the contract is broken, the clients can prove it was broken, and publish that proof.

Compared to decentralized consensus, a ledger-backed service provides the exact same level of auditability. It trades the interchangeability of hosts for a much cheaper operating model - no proof-of-work. Given the cost of PoW, I think that’s a huge win.

There are some downsides to losing decentralized consensus. A ledger-backed service could manipulate the order in which it handles requests, or reject some requests altogether, and clients would have a hard time proving it. You could combat that problem using a third-party proxy, which logs the attempted calls and notes the responses from the host. The other downside is that, without decentralized consensus, the only way to handle a misbehaving service is to stop using it - whereas Bitcoin can just ignore the misbehaving miner.

As a proof-of-concept, I wrote a ledger-backed server called NodeVMS which uses code from Dat to provide the secure ledger. (Dat contains a secure ledger implementation called Hypercore, typically used for distributing files in a p2p mesh. Here it’s used to distribute the state and activity log of the service.) VMS is not production-ready, but it demonstrates the core ideas of this design.

Consider the alternative

Before turning to proof-of-work or any form of decentralized consensus, think about the costs. Think about what you’re dedicating your users to. Ask yourself:

- Is it decentralized consensus you want, or just improved accountability and better trust?

- Am I certain that I need strict global consensus?

- Could I solve the ownership problem by using peer-to-peer publishing, e.g. with Dat?

- Could I solve the choice problem with configurable endpoints?

- Do I really need to burn all that energy to power my app?

I suspect that, for a lot of people, a service with a secure ledger is enough.

If you liked this post, be sure to check out my work with the Beaker Browser and it's companion project, the Dat protocol.

Thanks to Tara, Vito, Andrew, John, Brian, Mafintosh, and everybody in #beakerbrowser for their feedback and help writing this post.

Tweets: twitter.com/pfrazee

Code: github.com/pfrazee

Creating a peer-to-peer Web: beakerbrowser.com