Universal publishing and the Web's black boxes

January 3, 2018. @pfrazee

Just because something is accessible by browser does not make it part of the Web.

Adobe Flash was used widely as a plugin on the Web until recently, but it never became a Web standard. Browsers accessed Flash via the <object> tag, which acted as a portal to the user’s local installation. But because it was proprietary code and disconnected from the Web platform, it was essentially a black box.

Despite (mostly) moving past the days of plugins, the Web is still full of black boxes. Most activities— status updates, friend requests, searches, and upvotes—are provided by proprietary backends. Like Flash plugins before them, services that provide interfaces for these activities are black boxes: accessible by the browser, but proprietary and non-standard to the Web.

Universality and the Web

The Web was built to be universal; it’s a shared language for networked applications, with no attachment to any specific vendor. Universality establishes common behavior and helps guarantee open access, so that anybody can build a website. For something to be part of the Web it can’t be a proprietary black box. It must use an open, portable, and universal language.

As an example, <a> tags are universal. They work across domains, and codify a user action (navigation) which is implemented by all clients. An end-user can inspect the HTML and infer what an <a> tag represents, because it’s codified in a meaningful fashion as a standard HTML tag.

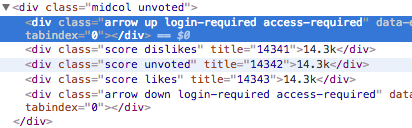

As a counter-example, Reddit upvotes are not universal. They only work on Reddit by connecting to its proprietary backend, and they are not codified in any universal language. (In fact they are <div> elements with the standard click behaviors overridden.)

Reddit's upvote HTML

Standard HTML tags are not the only way to establish universality on the Web, but they are one way.1 The test for universality is a simple question:

Would this feature function or have meaning if it were disconnected from a specific service?

If the answer is yes, then it is universal.

Standard publishing verbs

So, why don’t we have universal activities? Why is the Web still full of black box services?

In part, I think it’s because publishing on the Web has never been universal. Publishing depends on servers, and server behaviors are largely custom. There are no standard HTTP verbs for writing a file to a specific location, or for how to format the data in that specific file. Services interpret HTTP requests however they like within some broad standards. While that flexibility is a benefit for Getting Things Done(tm), it makes universality difficult to accomplish.

If servers were to adopt standard publishing verbs, we’d be a step closer to universal activities. Rather than using custom server behaviors, an application would read and write files using the standard publishing verbs. Those verbs would be usable by any application that understands them, and would make it possible to swap one service for another. Applications would then be able to coordinate by simply sharing their data schemas.

An imaginary Reddit clone

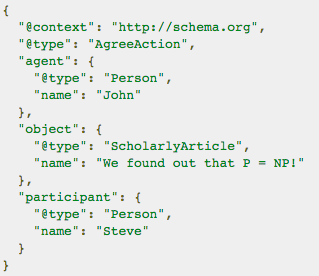

Suppose we were to write a Reddit clone with its own upvote control. The UI might still be a <div> with custom Javascript, but instead of talking to a custom backend, it would write a JSON file to a folder the user controls. That JSON file would declare its schema ("type": "upvote") and its target ("target": "https://pfrazee.hashbase.io").2

An http://schema.org/AgreeAction example

In our Reddit clone, we would now have a universal upvote. The published JSON file would have meaning as an “upvote” with no connection to a specific service, and it would work independently of its originating app. Another application could come along, read the upvote, modify it, delete it, or create a new one with no difficulty at all, because it knows how to use the standard publishing verbs. So long as the data schema is shared, the data itself is usable.

To summarize, standard HTTP verbs for writing files to servers would give us universal publishing, which could then be used to implement common Web activities without relying on proprietary services.

Blockers to universality

CouchDB came very close to universality

The closest I think we ever got to universal publishing was CouchApps. CouchDB has a set of HTTP endpoints which can be exposed publicly and which provide standard read and write behaviors (called the “2-tier architecture”). It also has hooks for custom javascript to provide aggregated views and input validation. At least one iteration of CouchApps made it possible to copy an entire application from one CouchDB server to another and have it work right away. Very cool!

Very sadly, it failed to catch on. In 2013, Nolan Lawson published an explanation of the promise and the challenge of CouchApps. Based on conversations I had with people in the Couch community, it appeared that in the end, user authentication was the major hangup.

It’s sad to see authentication be a blocker, but it isn’t the only challenge. My Reddit clone example glosses over a number of issues. It assumes the user has their own server and that apps can access it. It assumes authentication won’t be an issue, and that the UX of picking a server for your app won’t annoy and confuse users.

More critically, my example ignores questions about how to aggregate across many servers, ping users with notifications for important events like “friend requests”, or find content reliably. These are difficult issues to solve generally in federated networks, because they include complications like spam prevention, cache freshness, and the general cost of server administration.

In light of this, it’s easy to understand why the open Web stopped making progress toward universality. It seems like to solve anything, you need to solve everything. It’s very hard to increment your way to universality.

Thinking with Dat

With our work on the Beaker Browser, Tara and I have been promoting a peer-to-peer Web that uses the Dat protocol, so you might be surprised to see me talking about HTTP verbs on servers. The reality is, HTTP could be suitable for many of Beaker’s goals if users could reliably get access to their own servers, but that doesn’t seem practical.

The Dat protocol excites us because by embedding the server into the browser, it guarantees that users have access to their own servers.3 That not only answers our questions about having a server available, but also makes it easy to solve platform questions like authentication and app permissions access. Dat also has standard APIs for reading and writing files. It is designed for universal publishing.

Looking back on 2017, we found universal publishing with Dat to be a huge step forward, but still the first step of many. Developers too frequently asked,

- “How do our users find content and each other,”

- “How could I send a friend request,”

- and “How can I open chat channels?”

Previously, I proposed using non-standard services on top of the Dat network to solve these problems. While I still believe this is a good solution for handling large scale in the future, I think Beaker’s APIs need to pave a way toward universality. We should find fully peer-to-peer answers to these questions first. Otherwise, what’s the point?

The decision to make the Web an open system was necessary for it to be universal. You can't propose that something be a universal space and at the same time keep control of it.

1 Some notable efforts to create universal data encodings in HTML are RDFa and Microdata, both of which are supported by the huge Schema.org library. Schema.org and those encoding formats have been very successful for creating universal meaning, driven by Google's use-case of extracting data for search results. Unfortunately these tools handle meaning but not functionality, and we need both.

2 You might want to improve specificity with with JSON-LD.

3 Dat also excites us because it is versioned, works offline, syncs efficiently, scales automatically via peer seeding, and cryptographically addresses its files. In case you're curious: Dat is not yet a Web standard, but it's gaining adoption as we're now adding support for a second browser— first Beaker, now Brave. We're also beginning to write specifications for further adoption.

Thank you to Tara Vancil for her edits and feedback on this post.

Tweets: twitter.com/pfrazee

Code: github.com/pfrazee

Creating a peer-to-peer Web: beakerbrowser.com